On November 22, 2004, the UN General Assembly proclaimed May 8 and 9 as Days of Remembrance and Reconciliation. Since 2015, May 8 - Remembrance and Reconciliation Day - is the official memorial date of Ukraine for commemorating the memory of World War II victims.

75 years ago, this May day de jure became the end of a large-scale stage of World War II - the war against Nazi Germany. At that time, just under 4 months remained until the final completion of World War II, in which nearly 80% of the world’s population participated…

According to estimates of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, Ukraine, whose territory has been the scene of the military operations since September 1, 1939, when German planes first dropped a deadly cargo on peaceful Lviv, lost from 3-4 million military and undergrounders, more than 5 million civilians (of which about 1,500,000 Jews were the Holocaust victims); about 5 million people were subjected to various forms of forced displacement (deportations, evacuation, evictions, etc.). In general, the irretrievable losses of Ukraine amounted to 8-10 million people.

On the one hand, statistics graphically represents historical phenomena, allows us to evaluate their scale; it is the easiest way for a person’s natural need to compare something with something. At the same time, the lines of digital notation trap us over and over again. Numbers grade and, therefore, dehumanize the infinity of human tragedies. Operating with large and small numbers, we do not often think about what was the fate of this or that person, what was the life of his/her parents, wife or husband, children?

Back in school years, the author of these lines was amazed by one of the shots of the feature film dedicated to “secondary”, as it seemed to him, brought up by Soviet military memoirs and cinema, event - the landing of the allied forces in Normandy in June 1944. He was shocked not by the story of the search, the efforts and human sacrifices subordinated to one goal - to return at least one of three sons to the mother, but by the shots related to the integral part of US soldiers’ life - individual medallions for identification (primarily posthumous).

Trailer of “Saving Private Ryan” (1998) directed by Steven Spielberg. “Schindler's List” (1993, USA) is perhaps the most famous film on the Holocaust among his works.

The author was struck by the fact that, despite death, the memory of a soldier can be (and will be in the end) preserved thanks to one small detail. Even now, 76 years after the death of 9 837 American soldiers, we can find out their names placed in biographical directories or listed in the cemetery in Norman Colleville-sur-Mer.

In the permanent exhibition of Museum “Jewish Memory and Holocaust in Ukraine”, among other exhibits of World War II era, there is one of the little-known to a wide circle of visitors, symbol – an eyewitness of those dramatic years – a small plastic capsule – the so-called Red Army man’s medallion (“Mortal Medallion”) – a case in which a paper with information about a person was embedded. Such capsules, as a form of accounting, which allowed to identify a fallen soldier and accordingly preserve the memory of him, existed only until November 1942 (by the way, the height of fierce fighting in Stalingrad), after which they were canceled ...

In the permanent exhibition of Museum “Jewish Memory and Holocaust in Ukraine”, among other exhibits of World War II era, there is one of the little-known to a wide circle of visitors, symbol – an eyewitness of those dramatic years – a small plastic capsule – the so-called Red Army man’s medallion (“Mortal Medallion”) – a case in which a paper with information about a person was embedded. Such capsules, as a form of accounting, which allowed to identify a fallen soldier and accordingly preserve the memory of him, existed only until November 1942 (by the way, the height of fierce fighting in Stalingrad), after which they were canceled ...

The owner of this specific plastic container was Isaac Davydovych Tomashov (born in 1923), a native of Dnipro who lived on Dzerzhynskyi Street (now Volodymyr Vernadskyi Street), a musician mobilized into the Red Army in February 1941. Isaac Tomashov managed to survive in the crucible of war, receive state awards and witness the defeat of Nazi Germany. Fortunately, his capsule did not fulfill its intended purpose. But millions of military and civilian victims still remain in the category of “unknowns” and are unlikely to tell us their story, which will be probably different from the ceremonially varnished “reality”, which they (authorities) tried to introduce into the mass consciousness from the mid-1960s.

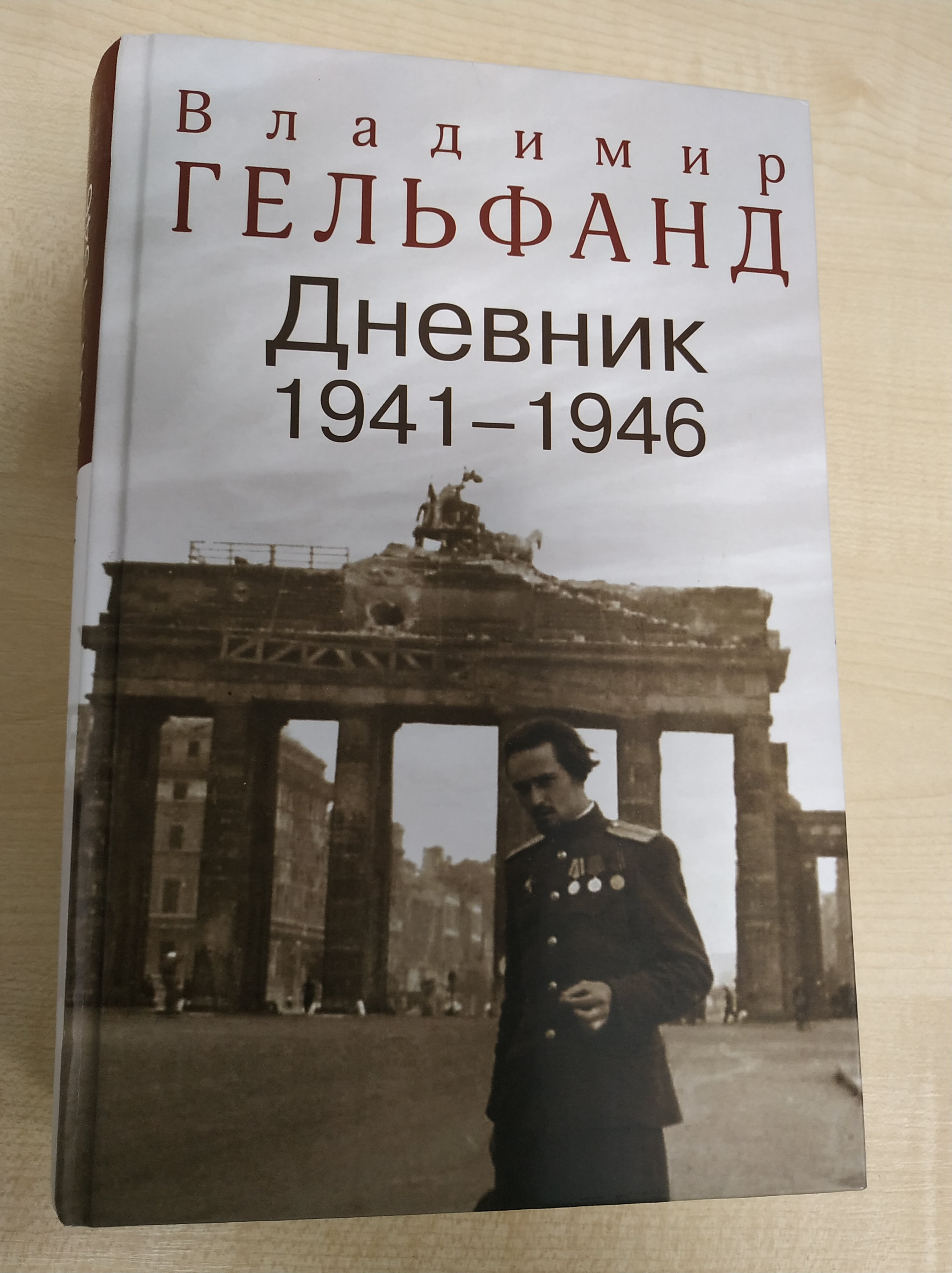

This artificially constructed memory of the war will have little in common with the reality of Volodymyr Gelfand (1923-1983), a student from Dnipropetrovsk who was mobilized into the Red Army at the age of 19. He will account for the encirclement near Kharkov in 1942, injuries, anti-Semitic attacks of individual officers. Despite this, he will fight and pass the war with honor, ending it in Germany with the rank of lieutenant ...

His “Diary” is the soulful reality of a somewhat naive young man, brought up in a communist spirit, who faced the harsh reality of war, human relations, betrayal, friendship and love.

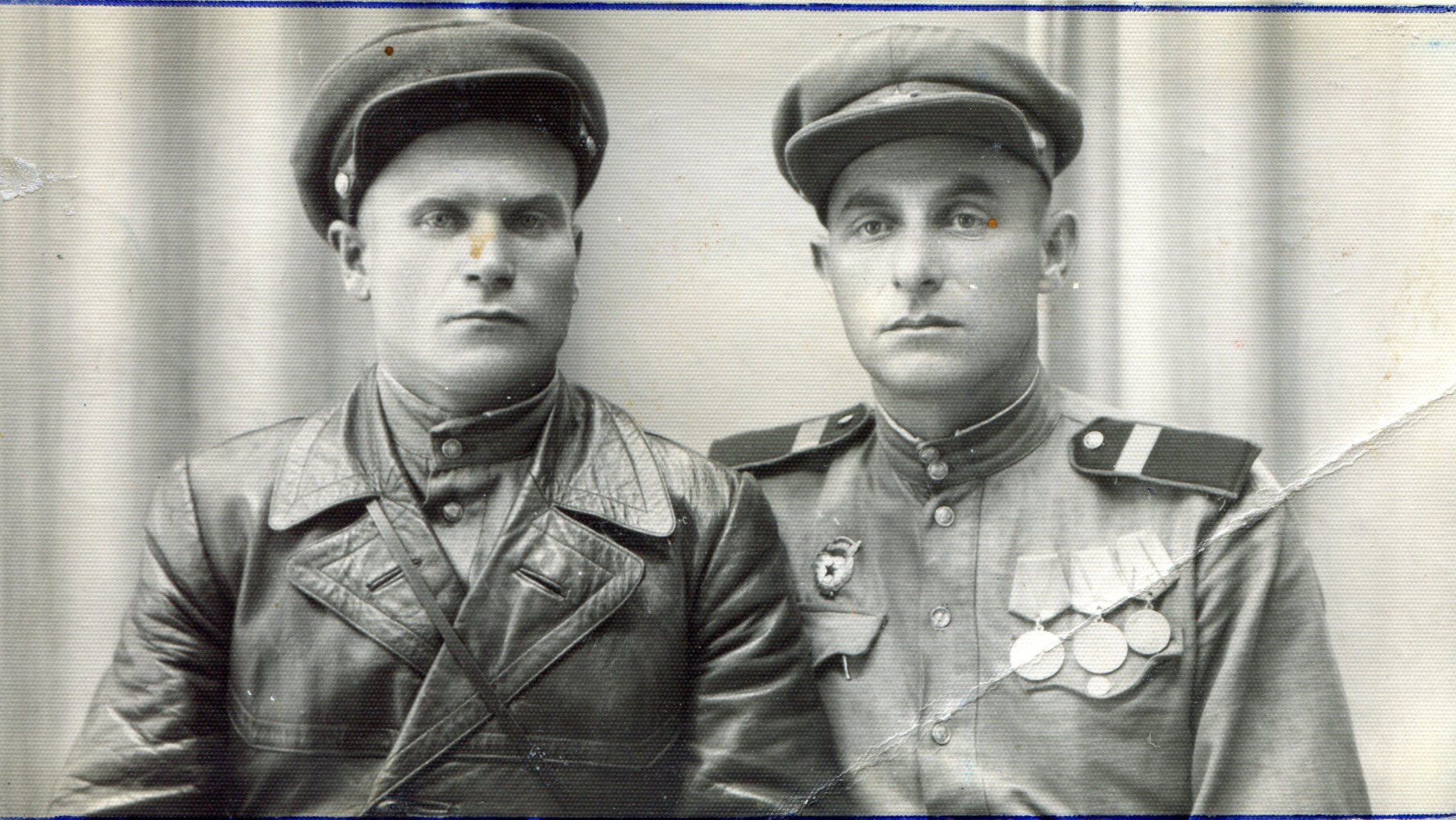

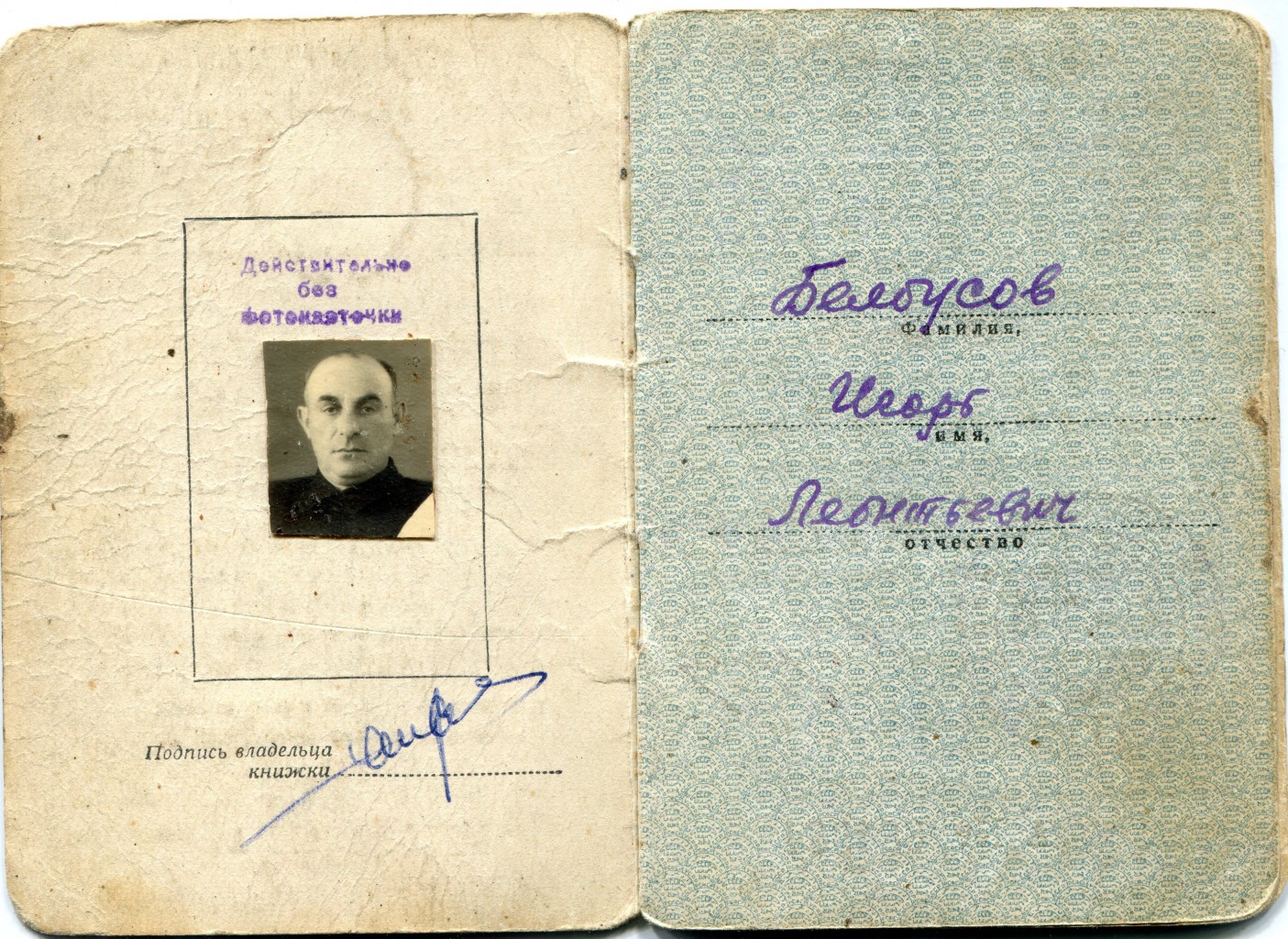

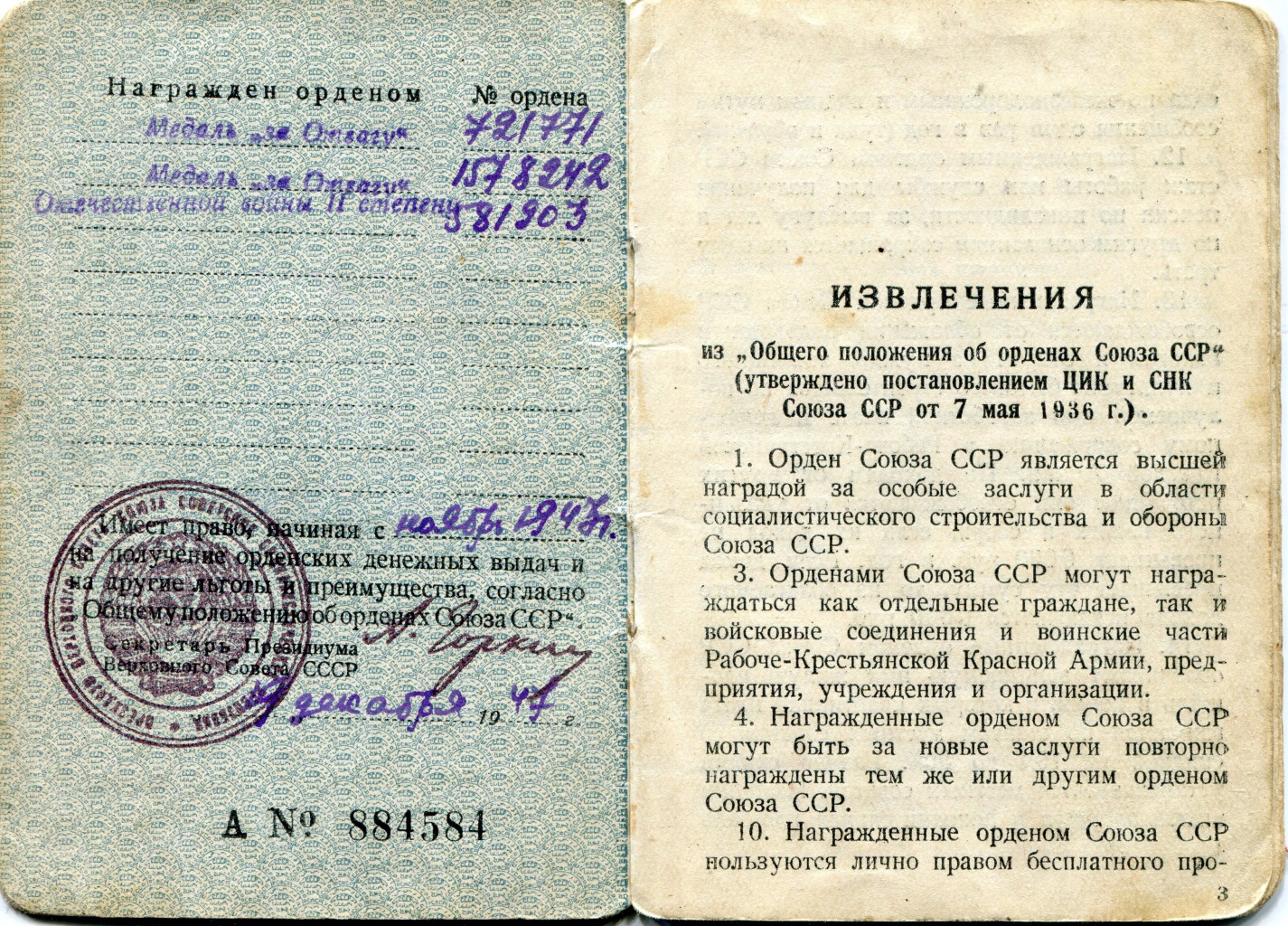

Did Israel (Igor) Bilousov (1908-1989), a signalman who moved to the western right bank in the cold Dnipro water at the end of September 1943 to provide communication to an assault group of daredevils who, despite the fierce fire of the enemy and the dubious intentions of the command, sought to survive and at the same time fulfill the combat order, feel like a hero? Why was he, awarded two medals “For Courage”, at first forced to renounce his Jewish name (and not remember about studying in a cheder), and make excuses for this before the party commission in the post-war years? Did he or his other brethren deserve popular ranting about the existence of the so-called “Tashkent Front”, although more than 500 thousand Jews, along with representatives of other nations, protected the world from Nazism?

Things, lines from front-line and evacuation letters, dry personal data of documents, photographs - they all continue to tell their completely different and at the same time elusively similar stories in which those, who are no longer with us, tell about their dreams, pain, joy and turmoil. I would like to believe that preserving the memory of this terrible War and the People, who were able to overcome it, will be their greatest Victory and our Respect.

Yehor Vradii