The Allied victory over Nazi Germany formally ended a six-year period of terror and terrible trials for millions of men and women. However, for certain groups of people who had been the targets of Nazi persecution throughout the occupation, the first post-war months and even years did not bring a final release from fear.

Six years of planned humiliation, discrimination and, ultimately, genocide had consequences not only on the catastrophic scale of the Holocaust in terms of the number of victims but also influenced the social atmosphere of the countries under German occupation. The practices of Nazi terror fueled centuries-old negative stereotypes that existed even before the outbreak of World War II. The material factor, which began to play an even greater role during the war, contributed to the development of anti-Semitic sentiments. After all, during the genocide, not only its German inspirers and organizers became rich, but also the civilian non-Jewish population of the occupied territories, which took into their own hands the movable and immovable property of Jews - shot in ravines or taken away in an unknown direction by railway trains.

It is impossible not to mention that the pro-communist government of Poland, formed by the will and direct instructions of the Soviet dictator, as well as the Polish state security organs, controlled by “colleagues” from the Soviet department, had representatives of Jewish origin in their composition. For Poland, which since 1935 had partly professed chauvinistic views in relation to ethnic minorities, Jews at the highest levels of power were a rare exception and an unnecessary confirmation of the “Jewish nature” of the communist regime. It should not be forgotten that even before the German occupation, the myth of the “Jewish commune” remained extremely popular in society, as well as the Soviet regime as its brightest. Obviously, the Nazis actively fueled this myth for their own purposes. It is also obvious that the expulsion of the Nazis from Poland and even the fact of Germany's surrender, unfortunately, could not fulfill the role of a magic wand, at the wave of which all the consequences of German propaganda, as well as anti-Semitic stereotypes that existed in Poland and in all European countries for many centuries, would disappear.

According to researchers, after the end of the war, there were between 50,000 and 60,000 Jews in Poland by the summer of 1945. For example, in Kraków, which during German rule was the “capital” of the occupation General Government, by September 1939 there were over 60,000 Jews living there. In contrast, in June 1945, 6,461 people of Jewish origin were registered in the city[1].

Most of them were those who were lucky enough to survive the occupation, as well as those who served in the Red Army (including the formally Polish but de facto subordinated to the USSR People’s Army) and those who were deported deep into the USSR in 1939–1941.

Returning to their native towns and villages, Jews faced not only material hardship, but also a negative attitude towards themselves from the non-Jewish population, most of whom did not expect their arrival. Conflicts arose repeatedly over ownership of property (primarily houses and apartments) that had belonged to Jews before the war. Domestic conflicts, coupled with the introduction of Soviet administrative practices, fueled anti-Semitic sentiments.

In the summer of 1945, local authorities in Kraków recorded a trend towards increasing anti-Semitic sentiment and conflicts based on hostility towards the Jews who had managed to survive. In most cases, the conflicts were related to everyday situations, but there were also cases of Jews being accused, for example, of kidnapping Polish children[2].

According to contemporaries, Shabbat gatherings in Krakow synagogues, which resumed in May 1945, were accompanied by constant excesses and attempts at petty hooliganism (verbal insults towards people heading to synagogues, throwing stones at them, etc.) directed against Jewish believers.

On Saturday, August 11, 1945, at approximately 10:30 a.m. during religious services around the Kupa Synagogue[3] on Medova Street, a crowd of teenagers gathered, as was now “traditional,” and “had fun” by throwing stones at the synagogue windows. One of the believers, a Jewish soldier, tried to calm the boys down with words, but received only ridicule in response. After that, he grabbed one of the boys (13-year-old Antoniy Niekay) and dragged him into the synagogue. The thug was beaten and a few minutes later ran outside, where he screamed and reported the kidnapping and attempted murder by Jews, as well as the bodies of other Christian children who were supposedly lying in the synagogue. This was the actual signal for the start of the pogrom.

Later, during the investigation, Antony Niekay testified about his participation in the events after he left the synagogue:

“[…] a policeman came up to me and told me to scream that they wanted to kill me. […] In the synagogue I saw Jews supporting a bloody boy [4], who might have been a Jew. I was scared of this and started running away, screaming because I was told [to do so – E.V.] because no one wanted to kill me”[5].

Quite quickly, a crowd of several thousand gathered near the synagogue, which began to destroy (and later set fire to) not only the synagogue, but also to beat Jews who tried to leave it. People who were unlucky enough to be on the nearby streets at that time also became victims of violence. In addition to the synagogue, the objects of the pogromists' aggression were also the building of the Jewish dormitory (26 Medova Street), which was located next to the synagogue, and the apartments in which, according to the attackers, Jews lived. Representatives of the police also took direct part in the pogrom. Under the pretext of “searching for weapons and Polish children,” they entered Jewish premises and, accordingly, opened the way for violence and robbery for the pogromists.

Only in the evening of the same day, thanks to the involvement of a unit of internal security forces, the authorities managed to take the situation under control. The exact number of victims (killed and injured) is still unknown. According to the investigation materials, the only fatal victim of the pogrom was 46-year-old Rosa Berger, who, during the German occupation, was able to survive the horrors of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp with her daughter. R. Berger was mortally wounded in her own apartment because of a shot by one of the police officers, who was trying to break the lock on the door in this way. According to researchers, the woman was not the only one who died that day in Krakow. Almost 150 people were detained for participating in the pogrom, including several dozen men in police uniform. 14 attackers were brought to criminal responsibility (sentenced to various terms of imprisonment – from 1 to 7 years).

Even though the authorities, public associations, and the official press condemned the anti-Semitic crime[6], the pogrom in Krakow was one of the episodes of the “war that continued” even after its official end. Less than a year later, in early July 1946, a similar tragedy unfolded in the relatively nearby city of Kielce, but on a larger scale in terms of the number of victims and the duration of the tragedy. For thousands of Jews, this was the final signal that they had to leave their homeland.

P.S. The surge of post-war anti-Semitism was not unique to Poland. Its manifestations could also be observed in Soviet Ukraine, even a few years before the start of the official anti-Semitic campaign, camouflaged as the “fight against the alienated cosmopolitans,” etc. We can assume that the USSR authorities, sensitive to “popular sentiment,” at some point decided to take control of anti-Jewish sentiment and use it for their own purposes.

Yegor Vradii

[1] Martyna Grądzka-Rejak. „Wybić ich wszystkich...”. URL: https://dziennikpolski24.pl/wybic-ich-wszystkich/ar/10490622

[2]For example, in the summer of 1945, rumors spread throughout Krakow that the remains of thirteen children, “killed by Jews,” had been found on Szyroka Street, located in the traditional Jewish district of Kazimierz.

3. The Kupa Synagogue, also known as the “Synagogue of the Poor”, was built around 1635. The synagogue was built with funds collected by Jewish artisans and small traders. This is where one of the names of the building comes from – Kupa (from the Hebrew “kupat-tzdakah” – a mug or container for collecting donations). After the synagogue was looted during the pogrom in August 1945, it was used as a place for baking matzah, and from 1951 its building was transferred to the Society of the Disabled as a warehouse. In 1991, the building was transferred to the Jewish Religious Community of Kraków.

[4] It is likely that the injured boy mentioned by Antoniy Niaky was a Jew who suffered injuries precisely because of Polish teenagers throwing stones at the synagogue windows.

[5] Quoted by: Roman Gieroń. „Wokół pogromu krakowskiego”. URL: https://przystanekhistoria.pl/pa2/tematy/zydzi/75062,Wokol-pogromu-krakowskiego.html

Translation of the quote – Yehor Vradii.

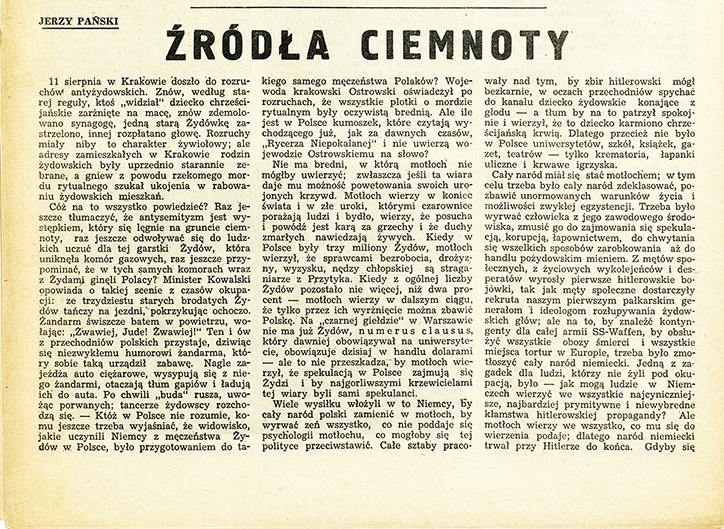

[6]For example, in the Moscow-controlled publication “New Horizons” („Nowe Widnokręgi”) Jerzy Panski's article “Sources of Darkness” appeared, dedicated to the pogrom in Krakow. It stated, in particular: “The riots in Krakow are not an isolated event. Similar excesses, although on a smaller scale, took place in other areas. After all, scale is a relative category and depends on the small number of Jews in a particular city. All these facts together are the focus of the reaction phenomenon that is occurring. A phenomenon that has recently been observed in Poland” (Pański Jerzy. Źródła ciemnoty. “Nowe Widnokręgi”, 1945. № 14. S. 14.)