It “opened” the historical 20th century and had an incredible influence on its further course. In our today's post, we will try to focus on one aspect of this event – the Jewish.

At the beginning of the war, the Jewish communities of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires actively supported the patriotic slogans of their governments. Of course, it is impossible to compare the situation of the Jewish minority in the Habsburg empire, where Jews enjoyed full civil rights and mostly represented an emancipated educated middle class, and in pogrom Russia with maximum legal restrictions for “foreigners”. However, even Russian Jews were not devoid of patriotic feelings and hoped that an active position in the war would ensure recognition for the Jewish communities at least in the future. Therefore, articles of a militant nature were published in the columns of the Jewish press, and prayers were held in synagogues about granting victory to the weapons of their country. The war was supported by many Jews who were abroad on various matters. Jewish students from Russia who had studied at Western universities returned home and voluntarily enlisted in the Russian army. Jewish veterans of the Russo-Japanese War also joined the army. Even more unexpectedly, the Jews of the Habsburg state supported the Austro-Hungarian government, since Russia, known for its anti-Semitism, was their country's enemy.

However, the longer the war lasted, the more the Jews felt like stepchildren in “their own” countries. The hostilities waged by the enemy became a real disaster for the civilian population living in the frontline regions. This especially applied to the Jews. Evacuation deep into the territories (even of the much happier sub-Austrian Jews, and even more so – sub-Russian Jews) destroyed the usual established ties between people, became a serious material test and emotional stress – not everyone could afford it, and if they did, they could retain their own ethnic tradition. So, the assimilation tendencies (Germanization, Russification) gained unprecedented acceleration.

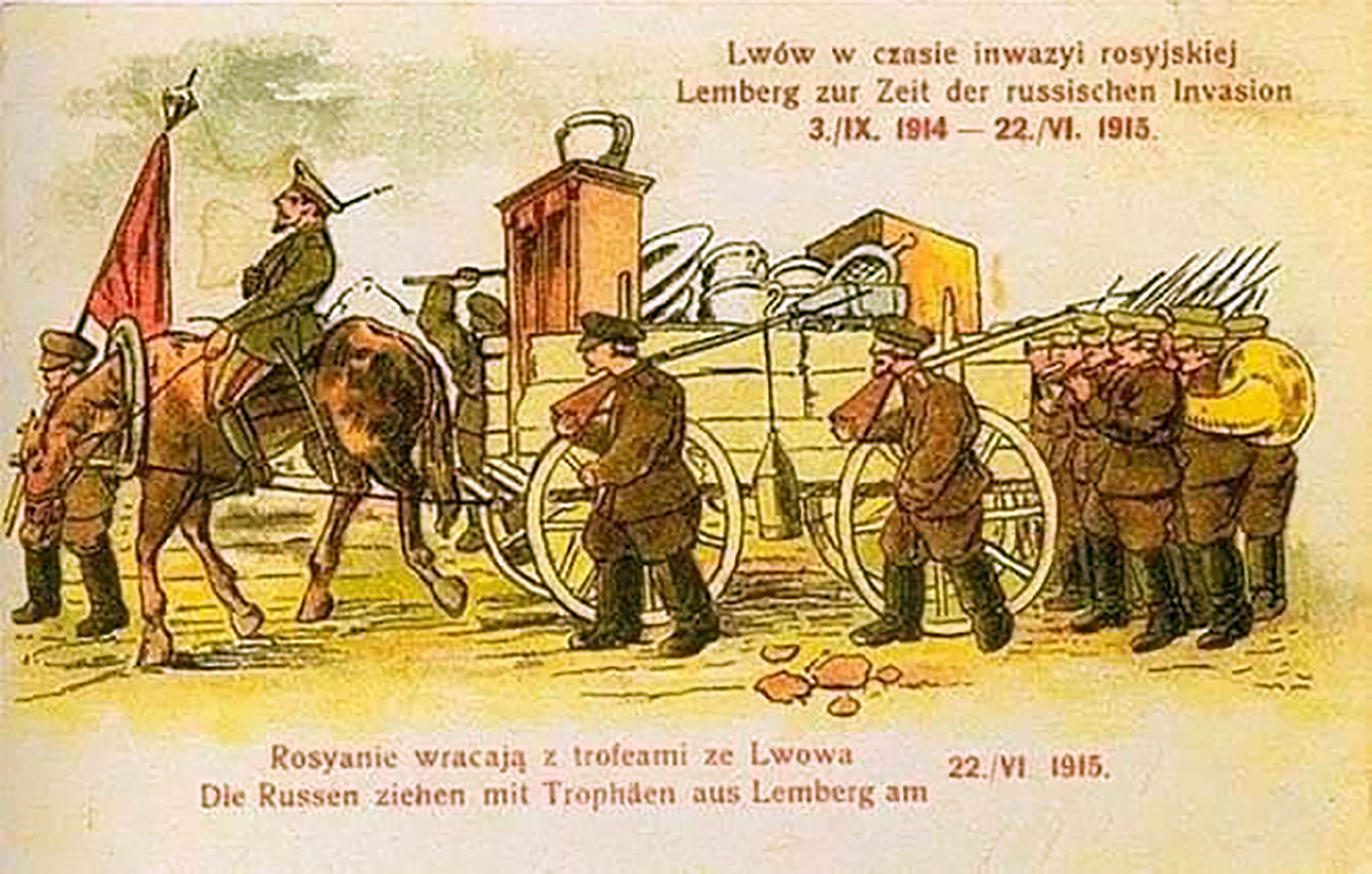

When the Russian army, after the victory in the Battle of Galicia (1914), entered Eastern Galicia and Bukovina, looting of Jewish shops, destruction of synagogues, desecration of sacred Jewish scrolls, economic extortion, and even the unjustified execution of Jewish hostages who were far from politics (of course, as enemies of “Mother Russia”). As a rule, wealthy, respected representatives of Jewish communities were chosen to play the role of hostages, who were kept in isolation under close surveillance. They could be executed if they were exposed as working for the enemy by one of their co-religionists.

Over time, under the pretext of protecting the front line from “potentially hostile elements,” the Russian military command deported Jews to remote provinces of Russia. The settlers were given neither money nor transportation; no more than a day was allocated for gathering. The transportation of many people took place in unsanitary conditions: the carts moved very slowly, there was a shortage of food and water. As a result, typhus, measles, and cholera spread (it was with epidemics that the extremely high casualties during the First World War among the civilian population, estimated at twice the front-line losses, were associated).

The best off were the immigrants who settled in cities with strong Jewish communities. For example, in Katerynoslav in 1915, 5,700 Jewish refugees were registered, in 1916 – 17,000. They were largely supported by Jewish charity. At the same time, the community was concerned about the employment of the most able-bodied part of the immigrants. For example, the “Society for the Assistance of Poor Jewish Artisans” created vocational training courses for workers in scarce specialties.

The most traumatic experience of exile was for representatives of the liberal professions – the depth of their social abyss was immeasurable. A striking example is the fate of the famous doctor, bibliophile, Zionist, and philanthropist from Białystok, Josip Khazanovich. During his lifetime, he sent over 63,000 books and documents to the library in Jerusalem, thus laying the foundation for the future Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem. In 1915, by order of the Russian military command, he was evicted from his hometown. In Katerynoslav, having no means of subsistence, he settled in a shelter for the elderly (Borodynska St., now Vartovykh Neba St., 24), where he soon died. J. Khazanovich is one of the heroes of the exhibition of the Museum “Outstanding Jews of Katerynoslav-Dnipropetrovsk-Dnipro”.

The situation became even more catastrophic after the defeats of the Russian army during the first half of 1915 – anti-Semitic sentiments in both the army and civilians intensified. The Russian military “confused” the Yiddish language, which the Jews spoke, with German, that is, the language of the enemy, and accused them of collective treason. Jews began to be accused of “espionage in favor of Germany”, of “revolutionary decomposition of the army”, and finally – of the banal “cowardice”, “weakness”, “less endurance” of Jewish soldiers; “warming up the hands in the war” (this was how they explained the high cost of products) of Jews in the rear. Thus, the military leadership tried to cover up its own incompetence, to explain the failures at the front and the troubles in the rear. The easiest way to do this was to artificially create a holistic image of the internal enemy. The practice of extrajudicial executions of Jewish hostages went beyond isolated cases. At the final stage of the war, the loss of control over the army and the collapse of the front contributed to the moral savagery of the soldier masses, who, having tasted the sweet taste of impunity, ceased to restrain themselves - they robbed, raped, and abused…

Thus, the Great War, the radicalization of interethnic relations began to destroy the traditional way of life of the Jews of both empires, strengthening, on the one hand, assimilation processes, on the other – the Zionist movement and left-wing radical socialist sentiments. So, long before the destructive whirlwinds of communism and Nazism, many Jewish settlements (shtetls) were already devastated during the First World War, because all the young people left or died.

The poison of xenophobia soon provoked a whirlwind of mass anti-Semitism in the territories of countries where the Great War was ongoing.

Olena Ishchenko