The solemn ceremony took place on the Champ de Mars in Paris. The soldiers broke the saber of the “traitor of France”, tore off Dreyfus’ officer’s epaulettes and other insignia. Meanwhile, the frenzied crowd enthusiastically shouted: “Death to the Jews!”, “Shame!” In response, the disgraced officer proclaimed: “I am innocent!”, “Long live the French army!”, “Farewell, France!”.

Captain Alfred Dreyfus was arrested on October 15 and charged with high treason. The basis for this was “indirect evidence” – a graphological examination of the handwriting on a piece of paper found in the wastebasket of the German embassy and handed over to the General Staff. It contained a description of intelligence regarding the rearmament of the French army, which was qualified as espionage information in favor of Germany. The specter of treason demanded an immediate reaction: the General Staff had to quickly purge themselves of the criminal and thereby save the honor of the army. So, a case was fabricated against the only Jew in the General Staff – Captain Dreyfus.

Alfred Dreyfus was born in Alsace, into an assimilated Jewish family of a wealthy manufacturer. After France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), Alsace was occupied by the Germans, and the patriotic Dreyfuss moved to Paris. Alfred did not continue his father’s commercial business; instead, he received an education and had a successful military career. Despite his Jewish origin, he ended up serving in the General Staff, the citadel of the French aristocracy. High professionalism, discipline, excellent memory, sense of dignity, and demandingness of himself and his subordinates – these qualities provided A. Dreyfus with a good position and career prospects. However, a shadow of alienation still lay over his relations with colleagues, brought up in the traditions of clerical anti-Semitism; so, everyone breathed a sigh of relief after the announcement of the name of the “culprit.”

Shortly after the trial, Dreyfus was sent to Devil's Island, located on the northeastern coast of South America; to serve life in prison (after the abolition of the death penalty, it was the heaviest sentence in the French courts). Dreyfus' opponents considered him incredibly lucky. When the convict was taken to the port to be put on a ship, he was accompanied by a crowd of Frenchmen who were wild with rage. On Devil's Island, Dreyfus lived with his guards, with whom he was forbidden to communicate. Every night, he was shackled so that the prisoner would not escape.

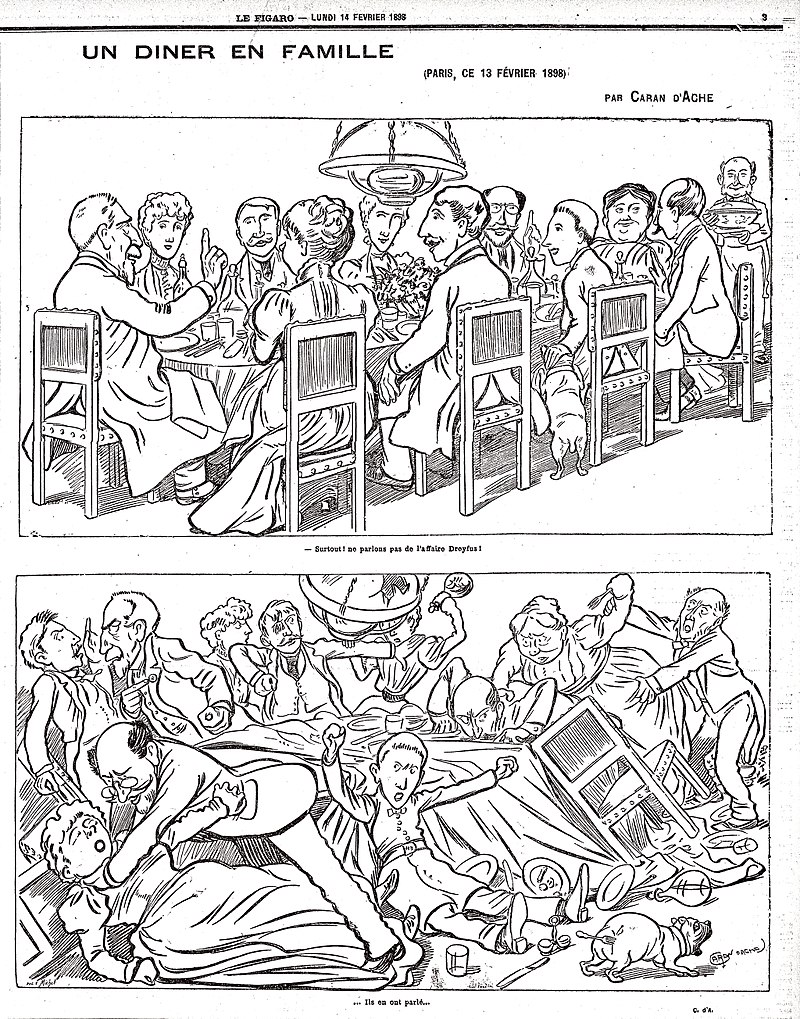

Meanwhile, French society split into two camps: anti-Dreyfussers and Dreyfussers. The anti-Dreyfussers (and they were the ones who initially dominated public opinion) were mostly characterized by emotional bias: for them, this process was a slap in the face received by the French army from the Jews with the assistance of Germany. “Deep” France, traumatized by the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, was persistently looking for the “culprit” of the failure, and it was easiest to find him on anti-Semitic grounds. Therefore, the anti-Dreyfussers did not delve into the legal arguments of the case so much – to them “everything was obvious” from the beginning. The Dreyfussers considered the accusation to be slanderous and proceeded primarily from the lack of motivation for treason in the accused. Indeed, it was hard to believe that an officer from a wealthy family, married to the daughter of a successful merchant; an impeccable patriot of France, who confidently walked towards the general's epaulettes, could be tempted by the fees of the German secret services. In addition, Dreyfus's defenders drew attention to the haste with which the investigation of the case was conducted and the insufficiency of the incriminating arguments. Based on the ideological “war”, friendships were broken up, family relationships were damaged... The process also split the French (and eventually the world) intellectual elite: Dreyfus was supported by writers E. Zola, A. France, M. Proust, E. Rostand, artists C. Monet, C. Pissarro; no less talented and famous writers J. Verne, A. Daudet, painters E. Degas, P. Cézanne, A. Matisse stood on the side of the anti-Dreyfusists.

While Dreyfus was serving his sentence, someone else's criminal espionage activity continued in the General Staff. A staunch anti-Dreyfusser, the head of intelligence at the General Staff, Colonel Georges Picard, accidentally stumbled upon the trial of a real spy. He turned out to be a staff officer, Count Esterházy (an avid duelist, an intriguer who had long been mired in debt – a corrupt swindler, but – “one of their own”, whom the staff officers did not want to betray). The case took an even more unexpected turn, because now it has become obvious that the innocent Dreyfus was convicted of a crime committed by someone else. The leadership of the General Staff, inclined to choose the side of “one of their own”, pressured Picard to keep his own discovery secret. However, the colonel, although he was an anti-Semite, turned out to be an honest man, and therefore insisted on a review of the case. Instead, he was sent to “far away” – to Tunisia, Algeria, to be as far away from Paris as possible.

A turning point that significantly strengthened the Dreyfus camp was the publication on January 13, 1898, of an open letter to the country's president by the prominent French writer Émile Zola in the newspaper “L'Aurore”. The living classic named all those involved in the accusation of the innocent Dreyfus to shield the criminal Esterházy. “I am waiting,” Zola ended his bold manifesto. And he waited – for a trial and his own accusation of slander against the French army. Zola escaped arrest by fleeing to England. And a wave of Jewish pogroms swept through France. Angoulême, Angers, Bordeaux, La Rochelle, Marseille, Montpellier, Moulins, Nantes, Paris, Rouen, Saint-Malo, Toulouse, Tours were engulfed in anti-Semitic actions: ordinary city dwellers looted Jewish shops, destroyed workshops, laid siege to synagogues, attacked Jews right on the streets. The bloodiest pogroms took place in Algeria. Everywhere, in most cases, the crowds did not act chaotically - with the help of the mostly anti-Dreyfus army and the police, they managed to organize them into disciplined paramilitary groups. The future stormtrooper units in Nazi Germany are involuntarily recalled…

Only in 1906 was A. Dreyfus found innocent. He was reinstated, given the next military rank, major, and a position in the General Staff; however, he left military service. During World War I, A. Dreyfus returned to the army and was awarded the Legion of Honor. During the Holocaust, Dreyfus' widow Lucy hid in a convent; their granddaughter Madeleine died in Auschwitz.

***In the crowd on January 5, 1895, Theodor Herzl, then a correspondent for a Viennese newspaper in Paris, found himself. He would later write that it was on that day that his faith in the progress of humanity, which supposedly could eradicate anti-Semitism, was shaken. “The Dreyfus trial turned me into a Zionist,” he said, realizing that the only way to solve the Jewish question was to create a Jewish state.

Olena Ishchenko