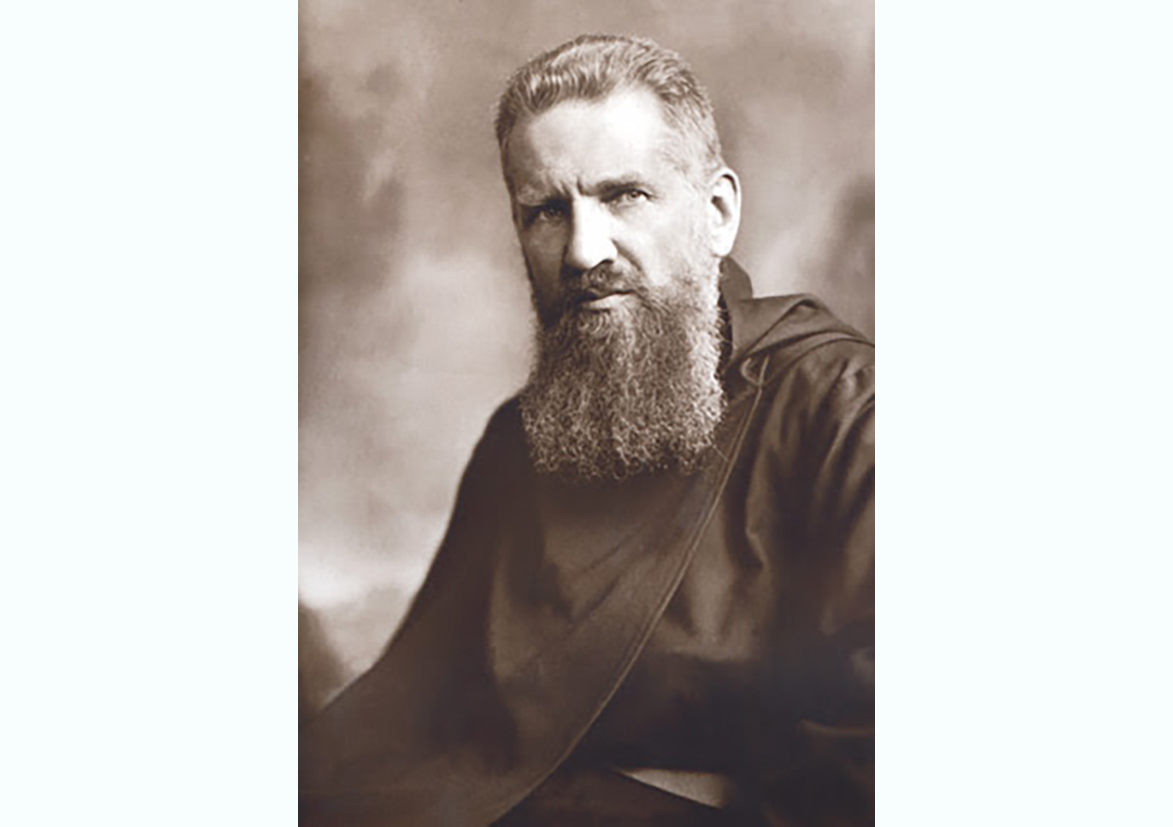

159 years ago, namely on July 29, 1865, Andrey Sheptytskyi was born – one of the most outstanding religious and social figures of Ukraine at the end of the 19th - the first half of the 20th century.

Museum “Jewish Memory and Holocaust in Ukraine” repeatedly told our readers about the vicissitudes of life and service of this man. The permanent exhibition of the Museum contains unique exhibits from the library of Metropolitan Sheptytskyi, and the Museum library contains dozens (in particular, the latest editions dedicated to the feat of A. Sheptytskyi and the clergy of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), who risked their own lives to save hundreds of Jews, condemned to death).

Today, I would like to dwell on several episodes from the life of an extraordinary figure of Ukrainian history, which, in our opinion, on the one hand, vividly characterize the spiritual principles of A. Sheptytskyi, on the other hand, demonstrate all the complexity of motivations and specific actions of an individual in a period of turbulent historical changes and tests.

Episode one. July–August 1934

On July 27, 1934, a militant of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Mykhailo Tsar, killed the director of the Ukrainian Academic Gymnasium, a former soldier of the Ukrainian Galician Army and the Army of the People's Republic of Ukraine, organizer and activist of the strata movement, Ivan Babii, in the middle of the street. The teacher, who has indisputable merits in the development of Ukrainian education, support of Ukrainian cultural projects in Lviv, according to the radical environment of the OUN, harmed the struggle for the restoration of Ukrainian independence. In particular, I. Babii hindered the campaigning activities of nationalists among school youth. According to some sources, he acted as a witness at the trial against Mykola Lemyk, an OUN activist, who in 1932 carried out a successful assassination attempt against Oleksiy Mailov, the secretary of the USSR Consulate in Lviv [1].

The murder of a well-known Lviv teacher shook not only the Ukrainian community of Lviv, but also the entire city. The funeral of I. Babi turned into a massive public manifestation of the rejection of terror to achieve political goals, even noble ones such as the election of the Ukrainian State.

Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi was one of those who resolutely denounced both the murder of Ivan Babii and the radical methods of fighting against political opponents, considering the latter to be frankly harmful to the Ukrainian movement and to human nature in general. In an article in the Lviv newspaper “Dilo” dated August 5, 1934, the metropolitan described his attitude to political murder as follows:

Director Babii fell victim to Ukrainian terrorists; a shiver of terror shook the entire nation. The best patriot, an honored citizen, a famous teacher, a friend known and appreciated by all, a guardian and good friend of Ukrainian youth are being killed in a treacherous way. They kill for no reason, except because they did not like the educational activities of the deceased. She was an obstacle in the criminal action of involving high school youth in underground work. If this is the case, then all decent and intelligent Ukrainians will fall at the hands of assassins, because there is no intelligent Ukrainian who would not oppose such a criminal action. […]

Among the unusual signs of the deceased was that rare sign that he produced even in his youth - courage. Knowing what he was exposed to, that sergeant of the Ukrainian army fulfilled a difficult duty for our children and, sacrificing his own good and the good of his family, did not leave his position. The soldier, who did not know how to escape, was shot from behind the raft not so much by an unfortunate confused and blinded killer, but rather by cowards fleeing from punishment, responsibility, opinion, just as in war cowards fled from the front” [2].

Episode two. End of June–beginning of July 1941

On the eighth day of the German-Soviet war, units of the Nazi army entered Lviv. In fact, the residents of the city immediately received a terrible confirmation of the truth they were so afraid of because of the will of the new occupiers: the opening of the premises of local prisons clearly testified to the inhuman crime of the Soviet authorities – the murder of thousands of people who were in prison. Unable to evacuate them to the east due to the rapid advance of the Wehrmacht, Soviet security officials chose the easiest and most obvious (from their point of view) option – murder.

The German authorities, having instantly orientated themselves in the situation, use these circumstances for the benefit of their own propaganda. Widely informing about the crimes of the Bolshevik regime, she places the emphasis as clearly as possible, emphasizing the supposedly Jewish nature of the communist state, and therefore, the direct responsibility of Jews for the crimes of the NKVD and the USSR in general. The fact that Galician Jews were among the victims of Soviet terror was not considered. Acts of public humiliation of Jews, to which the German Nazis resorted, opened the floodgates of emotionally colored violence, which quickly unfolded into a terrifying pogrom of the Jews of Lviv and other cities of Galicia. Unfortunately, the temptation of violence turned out to be irresistible for hundreds and possibly thousands of Ukrainians and Poles, who resorted to the most shameful acts – beatings, robberies, torture and murder.

On July 1, 1941, one of the spiritual leaders of the Jews of Lviv, Rabbi Ezekiel Levin, accompanied by several close companions, went to the Cathedral of St. George – the residence of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi. The son of the rabbi, Kurt Levin, recalled that his father asked him to translate the address to the metropolitan into Ukrainian:

I came to you, Your Excellency, on behalf of the Jewish community of Lviv, as well as a million Jews who live in Western Ukraine. At one time, you talked about your friendship for Jews. They always emphasized their friendly relations with us. I am asking you now, in a wave of terrible danger, to influence the agitated mass that started the pogrom. I am asking you to save thousands of Jews. Almighty God will reward Your Excellency a hundredfold [3].

A. Sheptytskyi was embarrassed by the violence in the streets and promised E. Levin that he would appeal to the German authorities to stop the persecution of Jews. He offered the rabbi himself and his relatives shelter in his own residence. However, in July 1941, no decisive action was taken (a public address and condemnation of the pogrom). From more than 80 years, we can construct interpretations of why the metropolitan remained silent. Perhaps he interpreted the pogrom as a terrible, but random and isolated episode that would not continue. Perhaps, like every person who has moments of weakness, he could not find the strength for an immediate and decisive reaction to the actions of the Nazis and those Ukrainians and Poles who linked their hopes with the new “liberators”.

At the same time, the events of the pogrom certainly had a significant impact on A. Sheptytskyi and his entourage and became the beginning of one of his most important life missions - saving the lives of persecuted and doomed Jews [4].

Episode three. November 21, 1942

If any of the Jews of Galicia had any illusions about the policy of the Nazi regime and the reactions of its supporters at the beginning of the occupation, in the fall of the second year of the German occupation, they were practically absent. Mass executions, ghetto, forced labor camp on St. For Yanivska, which for most of its prisoners could turn into a death camp at any moment, the deportations to Belzec destroyed any idea of the possibility of stopping the policy of total extermination of Jews.

The “devilish nature of Nazism” was also obvious to the metropolitan, who had unsuccessfully appealed to the Papal throne and the German authorities on several occasions, asking them to limit and stop the shameful murders and persecution of people. At the same time, he himself, as well as his closest associates, carried out a secret mission of mercy – they hid dozens of Jews in monasteries, temples and residences of the UGCC.

On November 21, 1942, Metropolitan A. Sheptytskyi addressed the faithful with a sermon dedicated to one of the most important commandments – “Thou shalt not kill.” In fact, he calls on every believer to have the courage to resist the sinister power of violence and to be brave and courageous, so as not to pollute oneself with one of the most terrible sins – taking the life of a neighbor:

Those who do not regard political murder as a sin deceive themselves and people in a strange way, as if politics exempts a man from the obligation of God's law and justifies a crime contrary to human nature. It is not so. A Christian is obliged to keep God's law not only in private life, but also in political and social life. A person who sheds the innocent blood of his enemy, a political opponent, is just as much a murderer as a person who does it for robbery and is equally deserving of the punishment of God and the oath of the Church [5].

A little less than two years later, on November 1, 1944, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi will complete his earthly journey. In March 1946, the Soviet authorities officially formalized a course of repressive policy against his church, and thousands of its faithful would become victims of Soviet totalitarianism. The memory of the greatness of the personality of A. Sheptytskyi, his actions will first become a taboo topic, and later Soviet propaganda will construct in the mass consciousness the image of an unprincipled collaborator, in part worse than the Nazis themselves.

However, the memory of the metropolitan remained alive. It was passed from mouth to mouth, it was written and spoken about outside Ukraine occupied by the totalitarian regime, it remained thanks to those people whom the metropolitan and people of His spirit and morality gave the opportunity to survive in times of the most terrible trials.

Yehor Vradii

[1] Олексій Майлов (справжнє ім’я Андрій Павлович Майлов) (1909–1933) – радянський дипломат. Попри обіймання формальної посади керівника канцелярії Консульства СРСР у Львові, на думку дослідників, був уповноваженим із нагляду за діяльністю радянських дипломатичних установ на території Польщі, а також одним із функціонерів радянської розвідки.

[2] Цит. за: Василь Расевич. Прокрустове ложе революційних націоналістів. Чому забуто настановче слово митрополита Андрея Шептицького? https://zaxid.net/statti_tag50974/ (Тут і далі при цитуванні збережено мову оригіналу).

[3] Цит. за: Жанна Ковба. Останній рабин Львова. Єзекіїль Левін. Львів-Київ: Дух і Літера, 2009. С. 99–100.

[4] З-посеред найновіших досліджень, присвячених темі рятування євреїв духівництвом УГКЦ, у бібліотеці Музею наявна книга львівського дослідника д-ра Юрія Скіри. Юрій Скіра. «Солід». Взуттєва фабрика життя. Львів: Човен, 2023. 224 с.

[5] Цит. за: Не убий. https://risu.ua/ne-ubij_n127648.