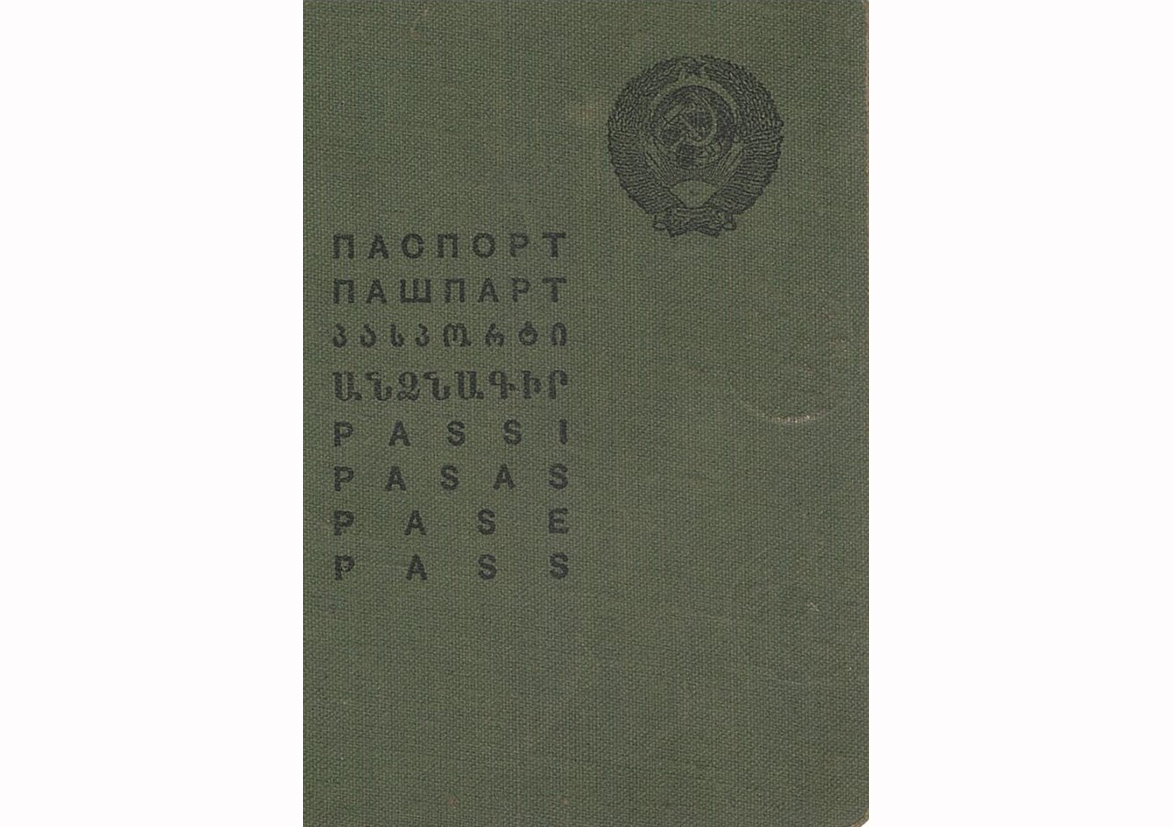

At the end of last year, the permanent exhibition of the Museum was replenished with several artifacts related to the history of the first genocide on Ukrainian lands in the 20th century – the Holodomor of 1932–1933. Among them is a passport of a citizen of the USSR of the 1932 model. More about it, as well as the context of the time with which the appearance of this item is associated, in more detail.

Older people may be familiar with the lines of Volodymyr Mayakovsky (1893–1930) dedicated to the Soviet passport. Written in 1929, the poem referred to a passport for foreign travel – a document as fantastic in the conditions of Soviet reality as the trip itself. Instead, citizens within the country identified themselves with various mandates, certificates and service certificates. Only on December 27, 1932, that is, a decade after the formation of the USSR, did the Resolution of the Union Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars No. 84 “On the Establishment of a Unified Passport System in the USSR and the Mandatory Registration of Passports” appear. On the last day of the same year, the corresponding document was also adopted for residents of Ukraine.

The reason for introducing a single passport system was the intensification of urbanization processes in the country – the growth of internal migration of rural residents to cities. On the one hand, this situation was facilitated by objective economic reasons, namely – the industrial modernization of the country, an increase in the number of enterprises and, as a result, the need for labor. On the other hand, the introduction of a single passport can be viewed in the context of the desire to establish state control over its own citizens and a policy aimed at the final subjugation of the Ukrainian peasantry.

According to the resolution, the official goal of establishing the passport system was the desire to “better record the population of cities, workers' settlements and new buildings and to relieve these settlements of persons not related to production and work in institutions or schools…as well as to cleanse these settlements of kulak, criminal and other anti-social elements who are hiding…”.

The resolution approved the “Regulations on Passports”, which in turn outlined the list of categories of citizens who were required to have passports. First, the passport privilege was granted to residents of cities, workers' settlements, transport workers, state farms and new buildings who had reached the age of 16. Initially, passports were issued for a period of 3 years. The document contained not only the usual personal information for us (date and place of birth, place of registration, marital status), but also information about nationality, social origin, place of work and military registration. At the same time, administrative and criminal liability was introduced for people who, without a passport and appropriate registration, would be in the territory of cities and other settlements with a mandatory passport regime.

Behind the brackets of bureaucratic formulations, a multimillion-strong peasant sea was deliberately left behind – people who in the early 1930s constituted most citizens of the “workers' and peasants' state”. It is noteworthy that the Soviet government undertook to introduce the passport system during the endless grain procurement campaign of 1932–1933. Under the conditions of artificial famine, which covered many regions of the Ukrainian SSR, almost the only hope for salvation was to escape from the collective farms and seek a better fate in the cities. They also felt a lack of food, but at least ghostly chances for salvation appeared. Children's homes and orphanages also operated in the cities, which, despite difficult circumstances, could save the lives of peasant children whose parents left them on the doorsteps of Soviet institutions.

Together with other repressive measures (the practice of “Black Boards”, etc.), Soviet passportization became one of the instruments of genocide, the victims of which, according to the most conservative estimates, were about 4 million people. The instrument had an international character, as it restricted the right to freedom of movement, which in the circumstances of that time often meant the right to life, regardless of the ethnic or religious affiliation of the peasant.

The absence of a small book with a gray, and later greenish binding, firmly tied the peasants to the land, the fruits of which were totally taken away by the state; it limited social prospects and doomed them to a beggarly existence and death. Passport discrimination against the rural population in various forms would last for more than four decades. After all, the village and its people in the USSR were long perceived as an inexhaustible reserve for socio-economic and social experiments. Only in 1974 were Ukrainian peasants able to obtain the cherished document for the first time on general grounds, like other citizens of the country.

Yehor Vradii