There is probably no other time of the year when we so often turn our thoughts to the assessment of time – a unique gift and a field of possibilities. The end of the previous year and the inevitable onset of the coming one force us to look at the calendar again and again. It is in its dates that we already see the outlines of what we want to do. And the calendar is not just columns of numbers that mean days, weeks and months – it is a reminder of events that are important to us personally and that define our identity.

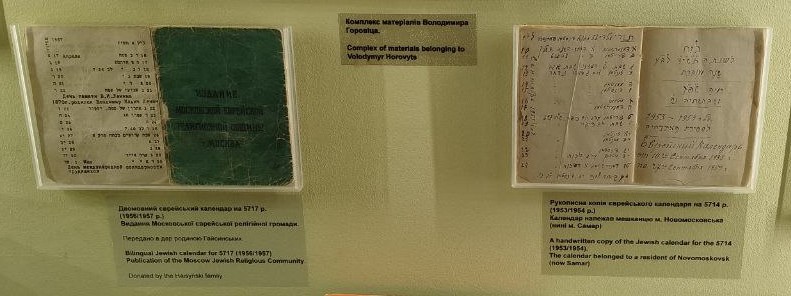

It was at the end of last year, 2024, that the permanent exhibition of Museum “Jewish Memory and Holocaust in Ukraine” was replenished with three interesting artifacts – Jewish religious calendars of the second half of the 20th century, which were used by Ukrainian Jews.

Two of them are printing publications of the Moscow Jewish Religious Community – almost the only Jewish association in the USSR that had the opportunity to officially print Jewish literature of religious content.

In addition to the familiar and usual for us contemporaries list of important dates of the Jewish religious calendar, an integral element of these bilingual (Hebrew and Russian) publications is a number of official secular dates, in particular, indications of the birthday of the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin) (April 22), the date of the Bolshevik coup of 1917 (in the publication “The Great October Revolution”) (November 7), etc.

Interestingly, the 1976 edition contains another element that was absent in earlier editions, namely, “Prayer for Peace.” The “prayer” itself was not something new for religious practice under Soviet conditions. In 1952, a conference of representatives of various religious denominations was held in Zagorsk (Moscow Region). The Jewish communities were represented at the conference by a native of Ukraine, Solomon Shlifer, the chief rabbi of the Moscow Synagogue (1944-1957). During his speech, S. Shlifer presented his own interpretation of the meaning of the word “Peace” for Jews: “For us, believing Jews, the word “peace” has, in addition to the general concept of peace, also a deep religious and symbolic meaning, since “Peace” – “Shalom” is one of the names of the Lord G-d, the Creator of the world, and we must fight for this sacred idea to the point of sacrifice.”

There are recorded cases when the prayer “For Peace” together with the “Prayer for the Government” was recited in a Moscow synagogue, and later in other synagogues in the country, as early as 1953.

It is obvious that such actions were intended to demonstrate the loyalty of Soviet believers to the ruling regime, which closely monitored religious life and at any convenient opportunity restricted the right to practice religion of its own citizens. The latter, being under constant pressure and surveillance, wishing to preserve those crumbs of religious “freedom” “guaranteed” by the Constitution of the USSR, were ready to adhere to the social etiquette established by the totalitarian regime.

To understand the context, let us give a few examples. In 1949, the 70th anniversary of the birth of the bloody dictator Joseph Stalin was celebrated as widely as possible in the USSR. There were probably no institutions, enterprises or organization where solemn events dedicated to this event would not have taken place. Religious communities of various faiths were no exception, forced to implement in their divine services mentions of a person who personified lack of freedom and terror. The Jews of Dnipropetrovsk (now Dnipro) did not escape this sad duty. Thus, on December 20, 1949, a solemn divine service was held in the only synagogue operating in the region at that time, and after it a report was read on the topic “On the life and revolutionary activities of J. V. Stalin”.

It is worth emphasizing once again that at that time the synagogue in Dnipropetrovsk was the only Jewish building whose activities remained officially permitted by the authorities. Repeated appeals from Jewish believers from other large cities in the region (Kryvyi Rih, Dniprodzerzhynsk (now Kamianske), Nikopol) either remained unconsidered or were returned with a refusal. One cannot ignore the fact that from the second half of 1948, the flywheel of an openly anti-Semitic campaign, camouflaged in the so-called “struggle against alien cosmopolitanism”, was gaining momentum. The oppressive atmosphere of the beginning of a new wave of repression forced believers to make a certain compromise with their conscience and resort to such loyal curtseys.

At the same time, in 1949, but in May, the Commissioner of the Council for Religious Cults under the Council of Ministers of the USSR in the Dnipropetrovsk region was able to prevent “calendar sabotage”. Thus, in a report to the republican and union leadership, he reported that a wall religious calendar was placed in the Dnipropetrovsk synagogue. The Soviet official was most concerned by the phrase “Leshana abaa Be Yisroel”, which supposedly ended the calendar. Not having sufficient knowledge, not knowing Hebrew and, probably, adhering to politically verified language structures, the Commissioner presented this phrase in a Russian translation: “Next year in Palestine” and reported on the successful elimination of the calendar and the explanatory work carried out in the community.

It is not surprising that the death of the dictator in early March 1953 was perceived by many people with relief and hope for liberalization. During this period that the third exhibit was made - a handwritten calendar for 7714 (1953/1954), which belonged to Isaac Medvedovsky, a resident of Novomoskovsk (now Samar), Dnipropetrovsk region. Most likely, the small circulations of permitted publications could not satisfy the needs of all Jewish believers. Therefore, people created handwritten copies for their own use. The material for the manuscript was an ordinary student notebook, folded in two. It is characteristic that I. Medvedovsky's calendar was monolingual (Hebrew) and did not have any signs of Soviet memorial officialdom.

The handwritten and printed calendars, placed in the permanent exhibition of the Museum, are a kind of reminder of the trials that befell the inhabitants of Ukraine and at the same time a confirmation of the preservation of traditions and Faith in the Almighty in the most difficult times.

The Museum expresses its sincere gratitude to the Haisinsky family, who transferred these important artifacts to the Museum, as well as to Mr. Abraham Yosif Yitzhak Karshenbaum for his assistance in replenishing our collection.

Yegor Vradii