November 9, 1938, was marked by mass violence against German Jews by the Nazi authorities in Germany and thousands of Germans who supported the anti-Semitic policies of the Hitler government. Several hundred people were killed in the events of one night (November 9-10); over 30,000 Jewish men were imprisoned in Nazi death camps; tens of thousands of properties belonging to Jewish communities and individuals were destroyed, damaged, and looted. In fact, the events of November 9-10, 1938, which were called “Kristallnacht” or “Night of Broken Windows” in newspaper headlines, marked the final transition of the Nazis from a policy of discrimination and segregation against Jews to a phase of undisguised violence against them. However, the acts of violence were preceded by a long propaganda campaign aimed at integrating Nazi ideology both in the public sphere and at the level of the individual consciousness of the average German.

In their quest for total domination of the information space, the leaders of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers' Party) were quite inventive when it came to channels of propaganda influence on the mass audience. In addition to traditional methods of disseminating information, such as radio, printed press, traditional visual advertising, etc., the Nazis actively used seemingly ordinary things that were part of everyday life of a person in the 1930s to spread their influence.

Since the mid-1870s, tobacco manufacturers in the United States, seeking to increase interest in their products, resorted to a new marketing move - inserting cardboard cards with images of celebrities - actors and actresses, athletes (mainly baseball players) into cigarette packs. Over time, the cards became collectible, as entire series were published dedicated to architectural monuments, sports and outstanding athletes, theater and film stars. In a situation where smoking was not a social taboo, the habit of inhaling harmful smoke was part of human existence, and moreover, mass culture actively popularized the bad habit and contributed to its transformation into a sign of a successful person.

Realizing that millions of people start their mornings by searching for a pack of their favorite cigarettes, the Nazis decided to use them as a channel of influence on smokers. Thus, in 1933, the first series of cardboard cards with images of Adolf Hitler and other leaders of the Nazi Party appeared, which were inserted into cigarette packs. The plots of the pictures were supposed to spread the message about the “unity” of the German people, the “new era of the Third Reich”, the ideal future under the leadership of the Nazi Party and the Führer in the most accessible way.

Later, these images would become the basis for special propaganda albums, which were distinguished by exceptional printing quality and were dedicated to various events that, according to Nazi propagandists, should be the basis for creating the only correct image of reality for the German people.

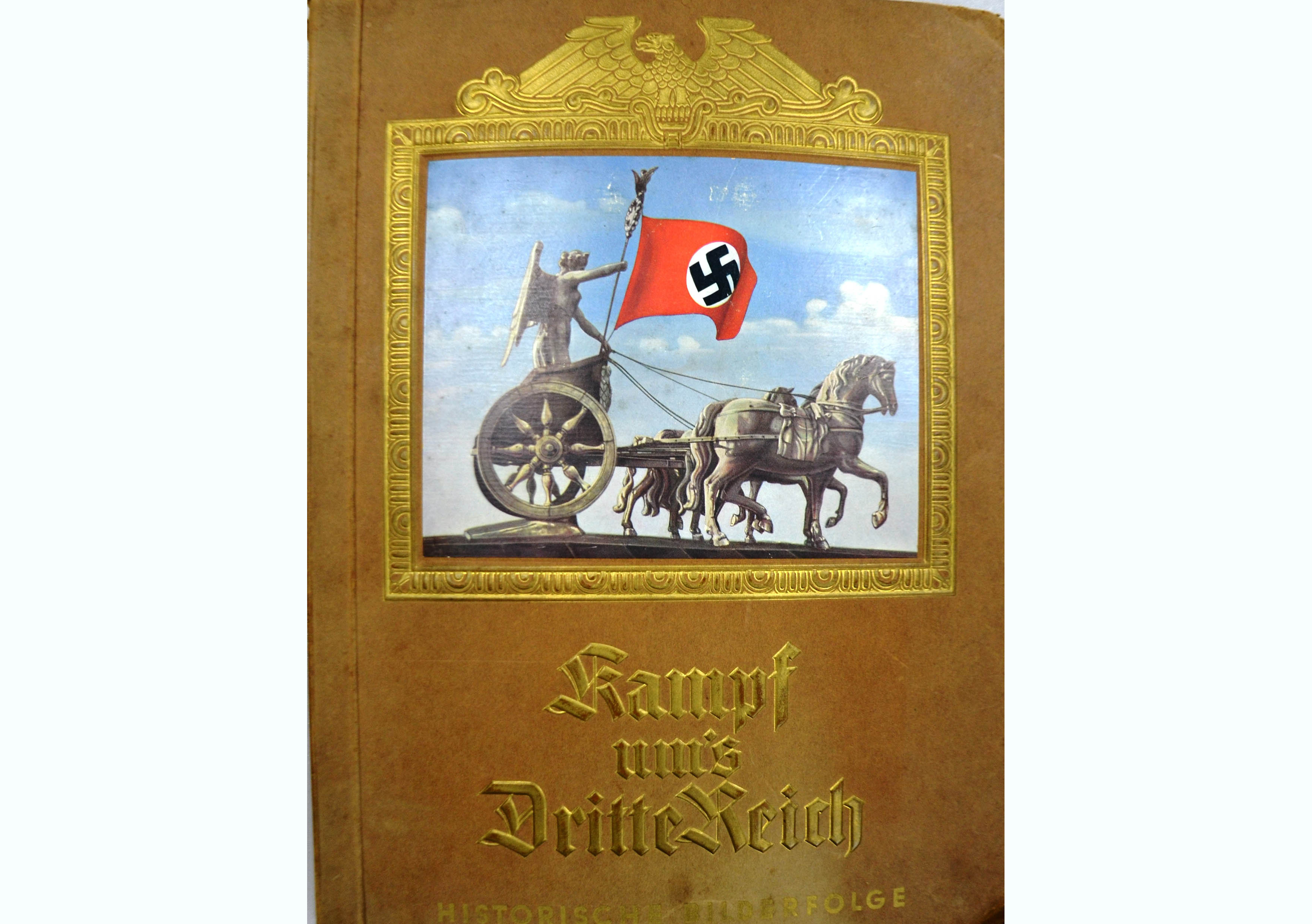

The exhibition of Museum “Jewish Memory and Holocaust in Ukraine” features several similar works of totalitarian propaganda, in particular the album “The Struggle for the Third Reich”, which was published in 1933, almost immediately after the NSDAP came to power in Germany.

The large-format color album edition had 92 pages and almost three hundred images (282 to be exact). Most of them, namely 277, were images from cigarette cards.

Analyzing visual propaganda images, it is worth noting the strong emphasis placed on the figure of A. Hitler as the “Führer of the party and the German nation.” Thus, almost a third of all images (a total of 82) are dedicated to him at different periods and in different guises: a soldier of the German Empire army, a political activist, a prisoner of Landsberg prison, a chancellor, an “ordinary man,” and “the best friend of German youth.” The latter is a favorite plot of propaganda materials not only of Nazi Germany, but also of almost all authoritarian and totalitarian regimes that cultivate the cult of the leader.

З-among other influential Nazis, the greatest honor to portray them was bestowed upon: Joseph Goebbels - Reich Minister of Public Education and Propaganda of Germany (8 images, the vast majority of which are individual); Hermann Goering – Chairman of the Reichstag (German parliament) (6 images); Ernst Röhm – Chief of Staff of the SA (assault units, the so-called “brownshirts”) (6 images). For the latter, such attention from the authors of the propaganda publication was a kind of “swan song”, because the following year E. Röhm, along with several other leaders of the assault troops, was destroyed on the personal order of A. Hitler. And subsequent editions of the album were published without any mention of the “machine gun king”.

Except for A. Hitler, it was this trio that was dedicated to separate sections of the album. However, if in the case of E. Rehm and G. Goering, the amount of information about them was barely half a page, then almost one and a half was devoted to the main inspirer of Nazi propaganda, J. Goebbels! Interestingly, in addition to him, another Nazi propagandist received the “honor” of being present together with the Führer – Julius Streicher, editor-in-chief of the vulgar propaganda newspaper “Die Stürmer” (“Stormman”) and newly elected (in 1933) deputy of the Reichstag.

The only figure who formally did not belong to the NSDAP circle, presented on the pages of the propaganda publication, was Field Marshal General Paul von Hindenburg, the Reich President of Germany. The latter was assigned the role of a kind of, almost sacred, intermediary, who carried out the transfer of the imperial inheritance from the “lost empire” in 1918 to the Führer of the “empire of the future” – the so-called “Third Reich”.

In general, a thorough analysis of the semantics of images, the messages embedded in them, as well as propaganda texts (including poetic ones) is a field for research not only into Nazi propaganda, but also into the phenomenon of totalitarian propaganda in general. Understanding its mechanisms, the “emotional pain points” it appeals to, the essence and forms of hate speech remain relevant today. After all, even now, totalitarian regimes, creatively applying modern technological achievements, strive to do everything to maintain power and spread their influence in the world. So, as in the past, images and words in the present become a prologue to violence in the future.

Yehor Vradii