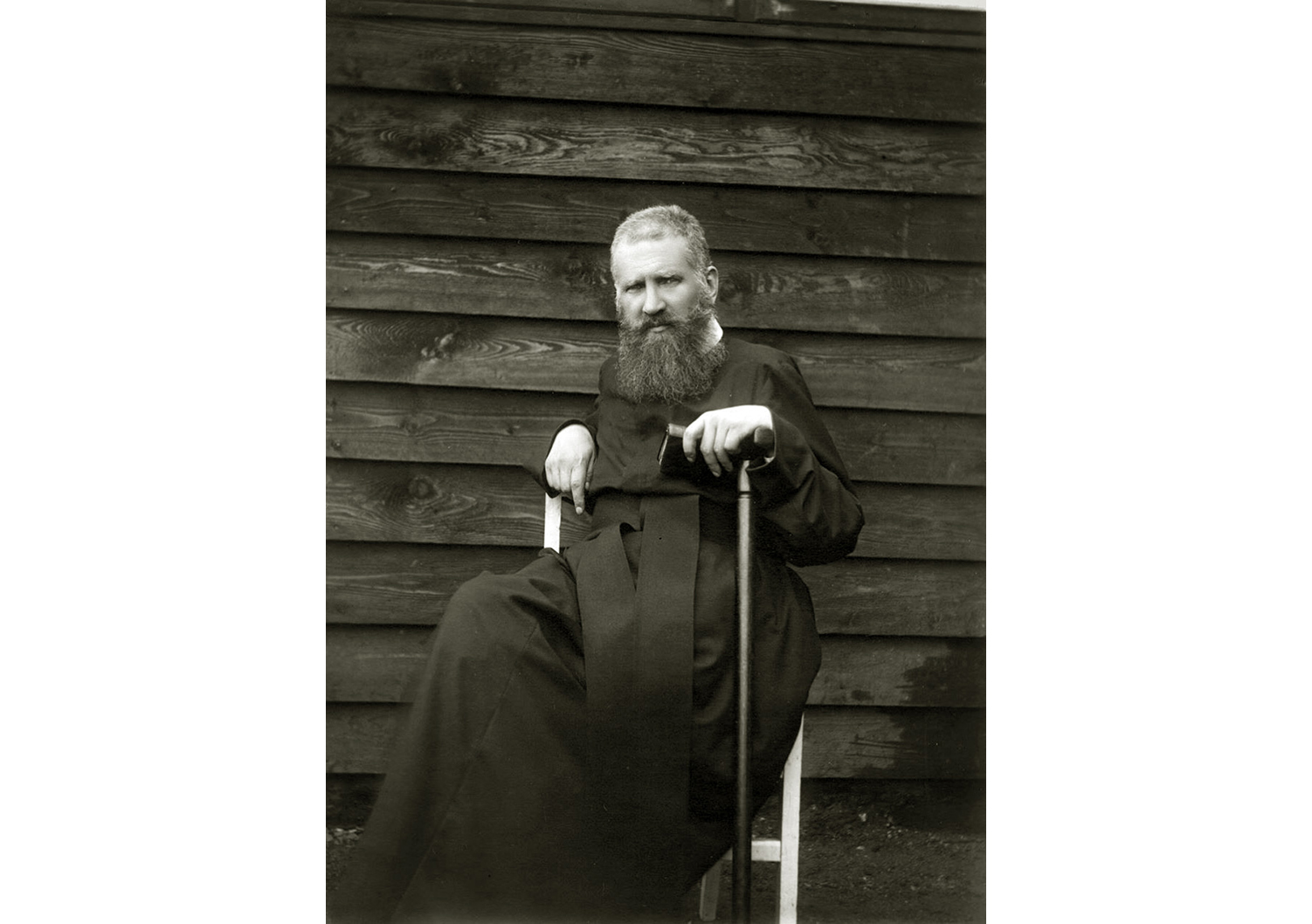

160 years ago, namely on July 29, 1865, Andrey Sheptytsky was born – one of the most prominent religious and public figures of Ukraine of the late 19th – first half of the 20th century, Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and spiritual leader of the Ukrainian people.

For almost 44 years, he was an unconditional moral authority not only for the clergy, but also for the intelligentsia and the common people. During World War II, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, together with his brother Klymenty, organized a system to save Jews from extermination. Thanks to it, the clergy of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church managed to save more than one life.

Andrey Sheptytsky (baptized as Roman Maria Oleksandr) was born in the village of Prylbych, near Lviv. He came from a noble ancient Ukrainian-Polish family, had the title of count. His brothers became part of the Polish national elite, occupied a serious place in the social system of Poland. But the metropolitan himself and his brother Klymenty considered themselves Ukrainians. Andrey Sheptytsky, being the spiritual leader of the Ukrainian people, also tried to consider the interests of Poles and Jews.

The future metropolitan received his primary education at home, and later studied at gymnasiums in Lviv and Krakow, was fluent in Ukrainian, English, French, German, Polish, Hebrew, and Latin. After graduation, he received the degrees of Doctor of Theology and Doctor of Philosophy. In 1888, he entered the monastery of the Basilian Fathers in Dobromyl and took the monastic name Andrey. In 1899, he was nominated Bishop of Stanislaviv, and in 1900, Metropolitan of Galicia.

Andrey Sheptytskyi was a reformer of many aspects of the life of the Ukrainian people. The living Ukrainian language was introduced into church services. Theological education was reformed, and the theological seminary in Lviv was reorganized. Sheptytskyi supported Ukrainian private schools, generously sponsored Ukrainian cultural and educational societies, and sent many student theologians to study in Rome, Innsbruck, Fribourg, and Vienna. He also took care of orphanages, shelters, and kindergartens, and financially supported scientific, educational, cultural, and artistic institutions, publishing houses, and public organizations. The building where the art school of the famous artist Oleksa Novakivskyi was located was purchased with the Metropolitan's funds. In 1905, Sheptytskyi founded the Ukrainian National Museum (https://nml.com.ua/),

purchasing a separate room for it. Thanks to Andrey Sheptytsky, the museum has one of the largest collections of icon painting in Europe. The Metropolitan transferred almost 10,000 items from his private collection to the museum's funds and maintained it at his own expense. Moreover, he supported the activities of the Ukrainian cultural and educational societies “Prosvita”, “Ridna Shkola”, “Silskyi Hospodar”.

It is worth noting that the metropolitan was an opponent of any manifestations of radicalism. This is evidenced by his reaction to the murder of the director of the Ukrainian Academic Gymnasium, a former soldier of the Ukrainian Galician Army and the UNR army, organizer and activist of the Plast movement Ivan Babiy on July 27, 1934. The crime was committed by a militant of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists Mykhailo Tsar right in the middle of the street. According to the radical environment of the OUN, the figure of I. Babiy, who developed Ukrainian education and supported Ukrainian cultural projects in Lviv, harmed the struggle for the restoration of Ukrainian independence. I. Babiy hindered the agitational activities of nationalists among school youth. Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky was one of those who resolutely condemned both the murder of Ivan Babiy and the radical methods of combating political opponents, considering the latter frankly harmful to the Ukrainian movement and to human nature in general.

After 1939, Western Ukraine was occupied by the Bolsheviks. From that moment until 1941, the processes of Sovietization took place, which the local population did not accept. Mass repressions began, including against figures of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Tens of thousands of Ukrainians were deported; thousands of residents were executed in NKVD prisons before the retreat of Soviet troops in 1941. During the same period, the youngest of the Sheptytsky brothers, Leon, and his wife Jadwiga, were executed by the NKVD in the family estate in Prylbychy. The inhuman crimes of the Soviet authorities deeply shocked the inhabitants of Western Ukraine, so people initially believed that the German army would contribute to the elimination of the Bolshevik regime and the achievement of Ukrainian independence.

In the first days after Germany's attack on the USSR, the metropolitan welcomed the Hitlerite army, because, like many Ukrainians, he believed that the Nazi troops would liberate Ukraine from the rule of the USSR, and, therefore, its territory would become sovereign. The “diabolical nature of Nazism” quickly became obvious to the metropolitan, who repeatedly unsuccessfully appealed to the Papal See and the German authorities, asking them to limit and stop the shameful murders and persecution of people. At the same time, he himself, as well as his closest associates, carried out a secret mission of mercy – they hid dozens of Jews in monasteries, temples and residences of the UGCC.

On November 21, 1942, Metropolitan A. Sheptytsky addressed the faithful with a sermon dedicated to one of the most important commandments – “Thou shalt not kill.” In fact, he called on every believer to have the courage to resist the sinister power of violence and to be brave and courageous, so as not to contaminate himself with one of the most terrible sins - taking the life of a neighbor.

Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky organized a campaign to save Ukrainian Jews, in which the following clergy participated: Archimandrite of the Studite monks Klymenty Sheptytsky; Abbess of the Studite Monastery Joseph, who headed all the nunneries; Rev. Fr. Marko Stek conducted large-scale work to produce documents for Jews that would identify them as Ukrainians; Priest Fr. Herman Budzinsky and Hieromonk Cyprian (Shulgan) took care of the fate of many Jews, including the sons of the chief rabbi of Lviv, Kurt and Nathan Levinas (https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/25426987.html);

Fr. Nikanor Deynega, Fr. Ivan Kotiv and Sister Monika Polyanska organized the issuance of “Aryan” documents to Jews, provided them with clothing and food; Fr. Mykola Galyant – head of the metropolitan office, together with secretary Volodymyr Hrytsai, hid Jews in churches. Andrey Sheptytsky personally entrusted Volodymyr Hrytsay with the care of Rabbi Kahane. According to the list compiled by David Kahane, more than 240 Ukrainian Greek Catholic priests took part in rescuing Jews. Thus, on August 14, 1942, about 200 Jewish children were secretly taken out of the Lviv ghetto and hidden in numerous monasteries in Lviv and the Lviv region. They were given documents, fake baptismal certificates, and given Ukrainian names.

It is interesting that the individuals who participated in the rescue operations were the Metropolitan's closest associates and shared his views on the reform of the UGCC. This circumstance explains the fact that it was mostly monks and nuns of the Studian order who participated in the rescue operations organized by the Metropolitan. Due to a serious conflict and fundamental differences in views on the liturgical reform, Andrey Sheptytsky did not involve the monks of the Order of St. Basil the Great in this matter. Unfortunately, among the ministers of the church there were those who were indifferent to the persecution of Jews and sometimes supported the “new order” and Ukrainians who tried to incorporate it.

Thus, during the German occupation, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky used the administrative structure of the UGCC as the main force of passive resistance to the Hitlerite government, and its network to aid Jews. The task of hiding persecuted Jews and providing them with other assistance was entrusted to all church ministers and parishioners.

After the Red Army entered Lviv, Andrey Sheptytsky transferred Jewish children from the Studite monasteries to the Jewish Committee, headed by Rabbi David Kagan, whom he had saved. Moreover, the metropolitan continued to send food and clothing to the Jewish Committee until all the children left Lviv or were adopted.

Andrey Sheptytskyi died on November 1, 1944, and was buried in the crypt of St. George's Cathedral in Lviv.

After the Lviv Cathedral in 1946, Soviet propaganda for many years consolidated negative images of the Greek Catholic priesthood, and from the late 1950s it presented Metropolitan Sheptytsky as an active collaborator, a spiritual inspirer of Ukrainian nationalists, etc. And, if we add to this the fact that some Greek Catholic priests consecrated volunteers of the 14th SS Grenadier Division, the image of the church and its leader will look quite ambiguous. Because of this, despite numerous appeals to the Yad Vashem Commission and irrefutable evidence of Andrei Sheptytsky's participation in saving the Jewish population, the metropolitan has still not been granted the honorary title of Righteous Among the Nations.

And if the figure of the inspirer and organizer of the system of rescuing the Jews of Galicia during the Nazi occupation is controversial, then some of his like-minded people (for example, Sister Joseph (Olena Viter), Father Marko Stek, Klimenty Sheptytsky, etc.) were recognized by the Yad Vashem Commission as Righteous Among the Nations.

The Museum “Jewish Memory and Holocaust in Ukraine” has unique items in its permanent exhibition - books from the personal library of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky with his facsimile autographs. And by visiting the Museum's library, everyone will be able to familiarize themselves with a wonderful selection of modern literature dedicated to these prominent Ukrainians.

Daria Yesina